|

| A slightly different perspective |

McArthur's Universal Corrective Map has always been my favourite depiction of Earth. As you can see, the map is oriented "upside-down" compared to what we are used to seeing. While learning about differences between the Mercator projections and equal area projections like the Mollweide projection helped me gain a more accurate understanding of the distribution of land on Earth, McArthur's projection yields a more philosophical insight and raises some interesting questions. Before I talk about the reasons I like this map, I'd like to give a little background information.

You may notice that Australia is at the dead centre of this map. The story goes that when Stuart McArthur was 12 years old he attempted to pass in a map oriented like this as geography homework. Following the rejection of his map by his geography teacher and sick of constantly being referred to as from the country at the "bottom of the world" or (more commonly) "Down Under", McArthur became resolutely determined to publish the world as he saw it.

The main thing that attracted me to this map when I first saw it (which was in the same geography class I previously mentioned) was that up until then, I had never questioned the relation between north-south and up-down. Though I recognize that the desire to separate Earth into two hemispheres is itself quite arbitrary, it has always made some sense to me to designate the north and south as the top and bottom of the globe due to both Earth's rotational axis and the direction of our magnetic field. McArthur's map made me question why we put north on the top of the map and not the bottom.

It turns out we have two classical-era (first/second centuries) scholars to thank for our now-traditional north-south/up-down map orientation. - a Phoenician named Marinus of Tyre and the more famous Roman-Egyptian Ptolemy. Though both these men (who may have been contemporaries) made revolutionary contributions to geography, their work was largely neglected after the decline of the Roman Empire. Almost none of Marinus' work survived into the present day, but his work served as the source material for much of Ptolemy's celebrated Geographica. Marinus of Tyre is credited as being the first person to divide the earth into a longitudinal and latitudinal coordinate system, a trait carried over by Ptolemy into Geographica. Their work provided the most complete picture of Earth that had ever been produced by the second century.

Sadly, we have no original copies of Ptolemy's world maps. Instead, we have carefully reconstructed maps based on the insane amount of detail of Ptolemy's text. You can see that the maps are really accurate - it boggles the twenty-first century mind that such precision could be achieved using second century technology.

Heaven and Hell - the socioeconomic divide and psychological impact of living "Down Under"

|

| Heaven and Hell as depicted in The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck (15th century) |

While the history behind cartography greatly interests me, the real thing that intrigued me about McArthur's Universal Corrective Map was McArthur's reasoning behind its creation. According to the few references to McArthur's map I have encountered online, 15-year-old McArthur was tired of feeling like a second-class human being on the "bottom of the world". Although we all intellectually understand that the south is no more the "bottom" of the world than any other randomly chosen point, it is easy to see how one might take being labeled a bottom-dweller as an insult. After all, language is filled with metaphors which reinforce the up-good, down-bad associations. such as "bottom feeder" and "bottom of the barrel" to describe an unsavoury character and a low-quality product, or "elated" and "high class" to express joy and status. Besides these figures of speech, we also see this association in religious mythology as in the Judeo-Christian Heaven and Hell or the Greek concepts of Mount Olympus and the Underworld.

The association of the abstract notions of good and bad with north and south have been examined by several teams of psychologists. One interesting article by Meier, Moller, Chen, and Riemer-Peltz called Spatial Metaphor and Real Estate: North–South Location Biases Housing Preference. Social Psychological and Personality Science (PDF) examined people's preconceived notions about the relation between north-south and good-evil using four different psychological tests. The results of these test indicated that not only do people associate north with good and south with bad, but that when given the choice of where they would live in a hypothetical city, most participants chose to live in the north. Additionally, their tests demonstrated that people are more likely to expect a rich person to live in the northern part of a hypothetical city while a poor person was generally assumed to have come from the south.

Meier, Moller et al. conjectured that the association between north and goodness stems from the tradition of depicting north on the top of maps. In order to test this, they modified their test to determine where a test participant would prefer to live in the northern or southern part of a hypothetical city by adding a note which described how in the hypothetical city the normal cardinal directions were reversed so that north was down, south was up, east was left and west was right. When participants were then asked to identify where they would like to live, the preference for north was greatly reduced.

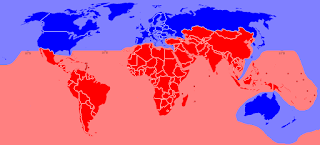

It is easy to see how the results of these tests relate to McArthur's map. Though we generally designate the various nations of Earth as being either first world, second world, third world or fourth world, the fact that we only ever hear about the first and third of these "worlds" reveals Earth's true socioeconomic divide. We could probably more sensibly group all nations into one of two groups, the "Haves" and the "Have Nots", as we like to say in Canada.

|

| Haves and Have-Nots |

For me, the effect of encountering McArthur's "corrective" map was that I was shaken from my culturally-induced assumptions about the world and forced to reevaluate my relative geographic importance. Perhaps in a world where McArthur's view was the norm we would all consider Australia, New Zealand and Indonesia to be at the "top" of the world, altering our perceptions of their relative importance.

I think that's the use of these maps. It's all too easy to fall into the psychological trap of associating the top of the map with the "top" of the world. The whole point I'm trying to make is that there is no top or bottom. It is so easy to say "white people come from the top of the world, dark people come from the bottom". While this seems innocent enough (especially the words "top" and "bottom" are simply being used as synonyms for "North" and "South"), pause and think of the actual psychological impact of that kind of statement. North, South. Top, bottom. Head, foot. When do these categories stop being simple descriptors and start being value judgements? What does it feel like for a Australian or African student who learns that he or she is on the botom of the world? What kind of an impact does being from the "top of the world" have for an American or German student? I think the answers to these questions could give us great insight into how the established power structures of the world are psychologically maintained in the cultures which created them.

Final point

Take a look at this photograph:

It's probably the most famous picture of Earth ever taken, called The Blue Marble. It was taken in 1972 by one of the Apollo 17 astronauts on the last trip humans ever took to the moon. If you look at it you'll see that the south pole is at the top and most of the land you can see is Africa, "upside down" from our traditional perspective. Before they could broadcast this image in the USA they had to orient it so that the south pole was at the bottom to meet the expectations of their audience. That is the power of maps - they can affect your worldview to the point that you will actually eschew reality in favour of an incorrect but more familiar perspective.

Anyway, if you've never encountered any of this stuff before, I hope it gave you a slightly different perspective on our world.

No comments:

Post a Comment